Why South Dakota Has the Nation’s Best Public Colleges

Also: Biden expands income-driven repayment, and Texas overhauls community college funding.

Welcome to The Tassel, FREOPP’s newsletter on higher education policy, written by senior fellow Preston Cooper. Each month, The Tassel dives into our latest work on higher education, along with a handpicked selection of research and articles from around the web that we think are worth your time. To manage your subscription preferences, visit your Substack settings.

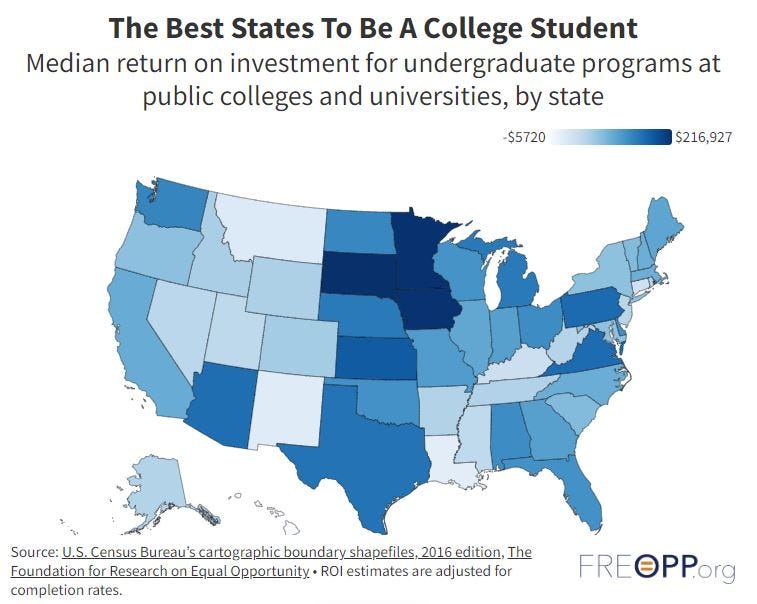

Unlike in many other countries, higher education policy in America is mostly set at the state level. Each state operates one or more systems of public colleges and universities, which have diverse structures and offerings. The decentralized nature of American higher education means that outcomes also vary across states. Using FREOPP’s measures of college return on investment (ROI), we’ve ranked the 50 state public university systems on the financial value they provide students.

Why South Dakota has the nation’s best public colleges

Public colleges in the Mount Rushmore State provide the highest ROI. Students who pursue a degree from one of South Dakota’s public institutions can expect to increase their lifetime earnings by $217,000, after accounting for the cost of tuition and time spent out of the labor force. That’s nearly twice the national median ROI of $118,000.

The secret to South Dakota’s success? A well-developed system of technical colleges such as the South Dakota School of Mines and Lake Area Technical College. FREOPP’s previous work on ROI has established that the value of college depends on what you study. To that end, most of South Dakota’s colleges offer two- and four-year degrees in fields where there is plenty of labor market demand, such as agricultural business and mechanical engineering.

Other states with high-value public university systems include Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, and Pennsylvania. I’ve previously written about the high value of the engineering school at Iowa State University, which buoys the Hawkeye State’s strong overall ROI. Kansas is another model for the nation, but for different reasons. Its public universities offer high-ROI degrees in fields which normally have a low return. For instance, journalism is not normally a lucrative field of study. But at the University of Kansas, the journalism degree is worth nearly $400,000.

Unfortunately, not every state can promise its college students a significant return on their investment. In Hawaii, for instance, a majority of degree programs at public universities do not have a positive return. Other states with typically low ROI include Montana, Louisiana, Connecticut, and New Mexico.

The good news is that policymakers in low-ROI states can take action to improve the financial value of attending public universities. One option is to tie some or all of the state funding that universities receive to the earnings that students realize from attending that school. If colleges increase student earnings, they get paid more. This creates a powerful incentive to focus on high-value programs, and deemphasize those that do not show a return on investment.

State governments should also ensure that public universities do not unduly restrict access to high-value majors. One research paper found that at the nation’s top 25 public universities, three-quarters of the most lucrative majors impose restrictions on who can enroll. This forces students into open-access but less remunerative majors. If public universities want to increase aggregate ROI, they need to open top majors to more students.

Notwithstanding politicians’ attempts to federalize the higher education system through free college and student loan subsidies, states still maintain significant authority to shape their own higher education systems. State universities provide the perfect laboratory for policy experimentation to improve the value of postsecondary education for all students.

What I’m writing

The Biden administration unveiled its long-awaited expansion of income-driven repayment last week. I bring you the details in Forbes. Undergraduate students will pay no more than 5 percent of their discretionary income towards their loans (down from 10 percent today), and those earning below 225 percent of the federal poverty line will pay nothing at all (the current threshold is 150 percent). These changes will slash student loan payments by more than half, and some students—especially those at community colleges—will never pay a dime towards their debts. That may sound nice, but it will create some awful incentives for colleges to push more loans on their students and use the resulting revenue to hike tuition.

A divided Congress took its seats this month, but there may be hope for bipartisan cooperation in a few areas. Also in Forbes, I explore three areas of higher education where Republicans and Democrats might find common ground. First, hold federally-funded colleges accountable when their former students are unable to repay their loans. Second, scale back the tax exemption for colleges with large endowments and use the revenue to top-up the wages of students who work while completing their studies. Finally, require accreditors—those independent agencies which ostensibly ensure quality in higher education—to explicitly consider student outcomes when deciding which colleges can access federal funding.

What I’m reading

Texas is planning to overhaul the way it funds community colleges to reward schools for producing more “credentials of value.” But the proposed funding formula is missing one critical metric: alumni earnings. In the Dallas Morning News, Annie Bowers and Prerita Govil argue that considering earnings will incentivize colleges to respond quickly to local industry needs and changing trends in the labor market. “Completing a program may earn a student a piece of paper,” write Bowers and Govil, “but it is not a sufficient indicator of the quality of the education or its workforce relevance.”

Income-share agreements have become politicized, but New Jersey’s Democratic governor is a fan of a similar product with a different name: outcomes-based loans. Over at Work Shift, Lilah Burke reports on a new public-private partnership in the Garden State that offers interest-free loans, which students repay as a share of their income. Those earning below $44,940 pay nothing. Of course, if the product helps students finance high-quality education, what proponents call it doesn’t really matter.

Utah Governor Spencer Cox plans to eliminate degree requirements for 98 percent of jobs in the state executive branch, following similar moves by the governors of Maryland and Colorado. Degrees have become a blanketed barrier-to-entry in too many jobs,” the governor said in a statement. “Instead of focusing on demonstrated competence, the focus too often has been on a piece of paper. We are changing that.”

The University of Austin wants to shake up the way higher education operates, with an eye towards lower costs. In an interview with The College Fix, President Pano Kanelos says his school will not require full-time faculty to hold doctorates, nor will faculty be tenured. Whether you agree with those specific policies or not, the fact is we desperately need more experimentation in higher ed, and the University of Austin is one of the few institutions willing to take risks. The school plans to admit its first undergraduate students in 2024.

What I’m doing

Over the holidays, I visited Chilean Patagonia with The Honorable Senator Shoshana Weissmann (I-East Virginia). Patagonia is full of craggy granite mountains, mighty glaciers, sapphire-blue lakes, llama-like guanacos, and noisy penguins. It’s one of the most beautiful places on Earth, and anyone who loves the outdoors should try to visit at some point.

Back in April, Shoshana and I coauthored a piece in National Review about how cosmetology licensing requirements saddle aspiring beauticians with unnecessary student debt. Nearly 90 percent of cosmetology certificate programs do not provide a financial return—yet hairstylists and manicurists are required by law to complete them anyways, even though there is little evidence the programs improve salon safety. Fortunately, states such as Virginia are starting to scale back education requirements for cosmetologists—and reducing student debt is a major factor in those decisions.