Why does the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile driver need a bachelor's degree?

Examining the rise in college degree requirements for low-wage jobs. Plus: Should the government write off defaulted student loans?

Welcome to The Tassel, FREOPP’s newsletter on higher education policy, written by senior fellow Preston Cooper. Each month, The Tassel dives into our latest work on higher education, along with a handpicked selection of research and articles from around the web that we think are worth your time. To manage your subscription preferences, visit your Substack settings.

If your interests involve hot dogs and road trips, rejoice. You can now apply to be the “Oscar Mayer Wienermobile Spokesperson,” a position which involves driving across the country in a “27-foot-long hot dog on wheels” representing the Oscar Mayer brand. The base salary is $35,600 per year. But there’s a catch: you’ll need a bachelor’s degree.

Perhaps $35,600 is an appropriate salary for a hot dog driver, perhaps not. I won’t pass judgement on that question. Historically, however, positions which pay at such a rate have rarely required college degrees. The Wienermobile job is emblematic of a worrying trend: the slow creep of bachelor’s degree requirements into lower-paid occupations.

Degree requirements creep into lower income brackets

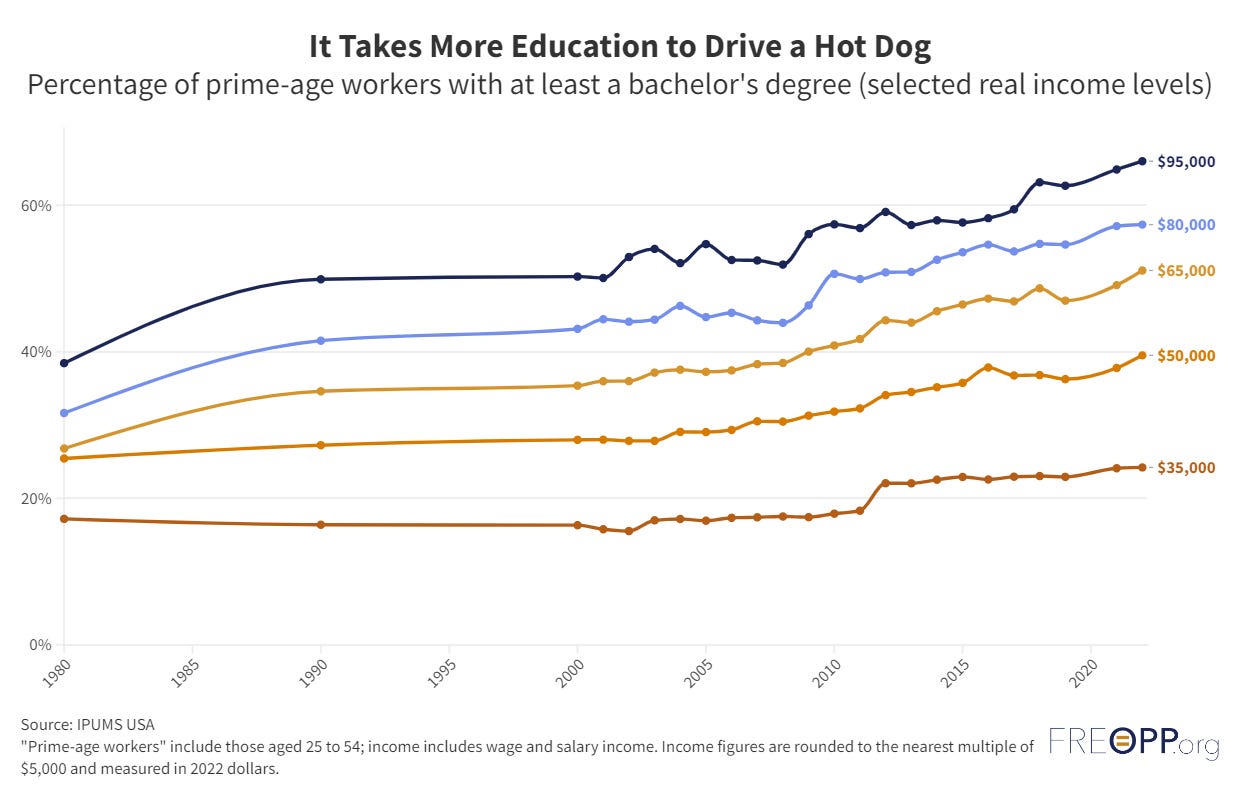

I documented some of these trends in a recent article for Forbes. In 2000, only 16 percent of prime-age workers earning approximately $35,000 per year (in today’s dollars) had a bachelor’s degree or higher. But in 2022, that proportion had risen to 24 percent, an increase of roughly half. The Wienermobile driver is not alone: more and more jobs in this salary range are demanding college degrees.

Earlier this year, I published a report on the phenomenon of “degree inflation”—the slow creep of college degree requirements into jobs that have not formerly demanded them. In 1990, for instance, just 9 percent of secretaries and administrative professionals held a bachelor’s degree. The role of a secretary has historically been a classic “learn by experience” job that functioned as a key career path for individuals with no education beyond high school. But now, 33 percent of secretaries have four-year degrees degrees, and an even greater share of job postings for this position request one.

Degree inflation has affected workers up and down the income ladder. Last year, 51 percent of prime-age workers earning approximately $65,000 per year held a bachelor’s degree or higher, up from 35 percent in 2000. Workers without a degree were once the majority among people enjoying this middle-class standard of living. Now, they are the exception.

Degree inflation hurts people with and without college degrees

In theory, going to college should make an individual more productive in the labor market, enabling her to command a higher salary. Thus, in a perfect world, rising college attainment moves workers from lower to higher income brackets, but the share of workers with a degree within each income bracket remains constant. But in the real world, more students going to college seems to have increased the education levels of lower-paid occupations.

The most obvious consequence of degree inflation is that it closes off job opportunities for the 62 percent of Americans who lack a four-year degree. But degree inflation also hurts those who finish college. Because the supply of college graduates grows faster than the availability of college-level jobs, many graduates end up “underemployed,” or working in jobs that have not traditionally required a college degree. Research shows that underemployed graduates face a large and persistent wage penalty.

The college graduate who ends up driving about in the Wienermobile for $35,600 per year may be able to relate. Graduates who earn salaries at that level will find it far more difficult to recoup the cost of their education—or repay their student loans. FREOPP’s analysis of college return on investment suggests that most students who finish bachelor’s degrees leading to Wienermobile-level starting salaries will be financially worse off for having attended college.

That’s one of many reasons to give colleges stronger incentives to ensure their students can earn back the cost of their education, and to invest in alternative pathways into the labor force that might serve Americans better—whether they aspire to drive a hot dog or not.

What I’m writing

Degree inflation is happening at the graduate level, too. (Forbes) In 2000, 11 percent of workers earning approximately $60,000 per year in today’s dollars held graduate degrees; now, the share is 17 percent. Given the hefty costs of graduate school, many of those workers won’t earn back the cost of their education. This problem is down in large part to federal student loan subsidies, which encourage colleges to offer expensive master’s degrees of dubious value. Sadly, a loan program meant to advance economic mobility has wound up enriching universities instead.

Should the government write off uncollectible student loans? (OppBlog) Nearly one million federal student borrowers have been in and out of default for more than two decades. There’s a strong case that these loans are uncollectible. One element of the Biden administration’s backup loan-cancellation scheme is a proposal that would cancel debt for most borrowers whose loans entered repayment more than 20 years ago, which would write off the loans of these long-term defaulters. But the administration’s proposal is far too broad, and will also discharge the loans of richer borrowers who don’t need the help.

What I’m reading

Students could soon receive federal aid for workforce training, under a bipartisan bill introduced last week by the Republican and Democratic leaders of the House Education and Workforce Committee. The proposal would allow students enrolled in short-term workforce preparation programs to access Pell Grants. To qualify, workforce training programs must increase their students’ earnings by at least the cost of tuition—a bar that most existing ones do not meet.

A new “workforce almanac” catalogs nearly 17,000 workforce training opportunities, defined as post-high school training options of less than two years. The project reveals the diversity of workforce training options in the United States, which include community colleges, trade schools, registered apprenticeships, federally-recognized training programs, and more. It’s the most comprehensive database of training providers released to date—which should say something about how seriously policymakers have taken workforce training in the past.

The college graduation rate ticked down slightly after years of improvements, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. Sixty-two percent of students who first enrolled in college during fall 2017 had earned a degree or certificate within six years. Completion rates are lowest at community colleges (43 percent) and highest at private four-year schools (78 percent).

What I’m doing

I was thrilled to join Wall Street Journal editorial board member Mene Ukueberuwa for a wide-ranging conversation on the value of college. Watch below:

A couple weekends ago I made a quick trip to San Francisco to visit an old friend. I also got to spend a few minutes at one of my favorite spots in the country: Pier 39, which is home to a boisterous colony of dog mermaids sea lions. The photo doesn’t do it justice, but there was a gorgeous sunset just beyond the Golden Gate Bridge. Watching sea lions bark at one another for extended periods is surprisingly entertaining, so I recommend stopping by if you’re in the Bay Area.

FREOPP’s work is made possible by people like you, who share our belief that equal opportunity is central to the American Dream. Please join them by making a donation today.