A pivotal moment for community colleges

Plus: A glitchy government form causes college admissions chaos, and an Ivy reinstates the SAT.

Welcome to The Tassel, FREOPP’s newsletter on higher education policy, written by senior fellow Preston Cooper. Each month, The Tassel dives into our latest work on higher education, along with a handpicked selection of research and articles from around the web that we think are worth your time. To manage your subscription preferences, visit your Substack settings.

It’s a tough time to be a community college. According to the latest numbers from the National Student Clearinghouse, in fall 2023 4.5 million students enrolled in community colleges, down 13 percent from fall 2019. Enrollment in four-year colleges is also down, but at community colleges things have really collapsed. And while the Covid-19 pandemic made matters worse, community college enrollment was already trending south before 2020.

Pretty much every member of Congress has a community college in their district, so policymakers are naturally worried. Democrats haven’t given up on making community college free, even though President Biden’s $109 billion scheme failed to gain much traction in an era of trillion-dollar fiscal deficits. Aside from cost, however, free-tuition plans are flawed for another reason: they fundamentally misconstrue the problems facing the community college sector.

Low tuition, but low completion rates too

Students aren’t turning away from community colleges because the price is too high. (Community college is already free for most students after financial aid, and the vast majority don’t need to take out loans.) As I argue in RealClearEducation this week, the problem isn’t price, but quality.

Just 43 percent of students who begin their studies at a community college complete any degree or certificate, and a paltry 16 percent successfully transfer to a four-year university and earn a bachelor’s degree. Economic outcomes aren’t great either. According to the College Scorecard, community college students earn just $33,000 six years after first enrolling, compared to $45,000 for students who choose public four-year colleges.

Unfortunately, there’s little sign things are getting better. A long-term study released this week found little improvement in community college completion rates over the past seven years. Another analysis found that community colleges tend not to increase their capacity to provide instruction in high-need fields, even when those fields experience a surge of labor market demand. Given this backdrop, it’s unsurprising that students are losing faith in the power of community college to unlock a better life.

Changing the incentives

One group of community colleges is an instructive exception to the rule, as I point out in a blog post at FREOPP. Two-year schools with a vocational focus have fully recovered their enrollment losses since the pandemic. Enrollment at these schools is 4 percent above 2019 levels—a better performance than any other group of two-year or four-year schools.

Students are increasingly interested in programs at community colleges that will help them get jobs. These include computer science (which has added 23,000 students since 2019), vehicle maintenance and repair (9,000), electrical and power transmission installation (8,000), licensed practical nursing (4,000), and precision metal working (2,000).

Policymakers have started to realize it’s not enough simply to increase funding for higher education and hope that solves its problems. Governments need to change incentives. Funding formulas should encourage colleges to add programs in fields with a strong return on investment. Policymakers’ duty to set up the right incentives is especially acute at community colleges, as three-quarters of their revenue comes from the government.

Several states are making moves. Texas is moving ahead with a plan to link appropriations for the state’s community colleges to the number of graduates who find good middle-class jobs, among other metrics. Pennsylvania’s Democratic governor also wants to tie college funding to performance. In North Carolina, the impetus for an incentives-based funding structure is coming from community colleges themselves. At the federal level, the House Education and Workforce Committee approved a bill to create a national performance funding scheme for colleges (paid for by trimming student loan subsidies).

Community colleges face a pivotal moment. Schools which don’t make changes could see their student numbers continue to slide. But those that successfully build up career training programs in high-demand fields may turn their enrollment crisis into an opportunity.

What I’m writing

A glitchy government form throws college admissions into chaos (OppBlog). The 2020 FAFSA Simplification Act, a longtime priority of Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), directed the Education Department to create a shorter form for college students to use when applying for federal aid. Three years later, the launch of the new FAFSA is a disaster, with experts calling the form “practically unusable.” There are several outstanding issues with the new FAFSA, including some that leave students unable to complete the form at all. The number of completed FAFSAs is less than half of where it should be, given past patterns, and college financial aid decisions are likely to be delayed by weeks or months. The Government Accountability Office has opened a probe into the chaos. One possible culprit: the Education Department’s capacity is overstretched thanks to its adventures into partisan policymaking, such as forgiving student debt by executive fiat.

What I’m reading

Dartmouth College is again requiring applicants to submit SAT or ACT scores, after going test-optional during the pandemic, writes David Leonhardt of the New York Times. Dartmouth’s internal analysis suggested going test-optional was hurting its ability to recruit qualified low-income students. Disadvantaged students with SAT scores “in the 1400 range” (i.e., great but not perfect) don’t submit their scores under test-optional policies. This leads the admissions office to miss low-income applicants who are nevertheless “excelling in their environment.” A return to requiring standardized tests will, Dartmouth hopes, improve its socioeconomic diversity.

Virginia is set to ban legacy preferences at public universities, in other college admissions news. A bill to block public institutions in the Old Dominion from giving preferences to the children of alumni unanimously passed the Virginia state legislature, and Governor Glenn Youngkin is expected to sign it. The effort marks a rare area of bipartisan agreement in higher education policy.

Why have Americans lost faith in the value of college? Longtime Wall Street Journal reporter Doug Belkin writes a longform essay on how the “college for all” promise fell apart. Fierce resistance to change in the academy is a reason that colleges have not adapted to the demands of the 21st century. "Many university presidents who pushed for new programs, the faster adoption of technology or the removal of undersubscribed majors faced no-confidence votes from their faculty,” Belkin writes. Students, who largely want college to prepare them for the jobs of tomorrow, have become disillusioned.

The real student loan crisis is in graduate education, writes Emma Camp for Reason. In 2006, Congress removed all effective caps on federal lending to graduate students, which caused tuition to balloon and universities to set up a number of flashy but low-quality master’s degree programs. Camp profiles Heather Lowe, whom the University of Southern California aggressively recruited into its online Master of Social Work program. After borrowing $90,000 from the federal government to finish a degree she hoped would lead to a better life, Lowe is earning the same salary she did before enrolling.

Politicians misperceive ordinary Americans’ access to higher education, but not in the way you’d think, says political scientist Adam Thal in an interview with the Niskanen Center. Politicians “overestimated how difficult it was for people in the state to access higher education,” says Thal. Moreover, “they thought that people were going into more debt to get into college than they actually were. So they overestimated the scale of the problem.”

What I’m doing

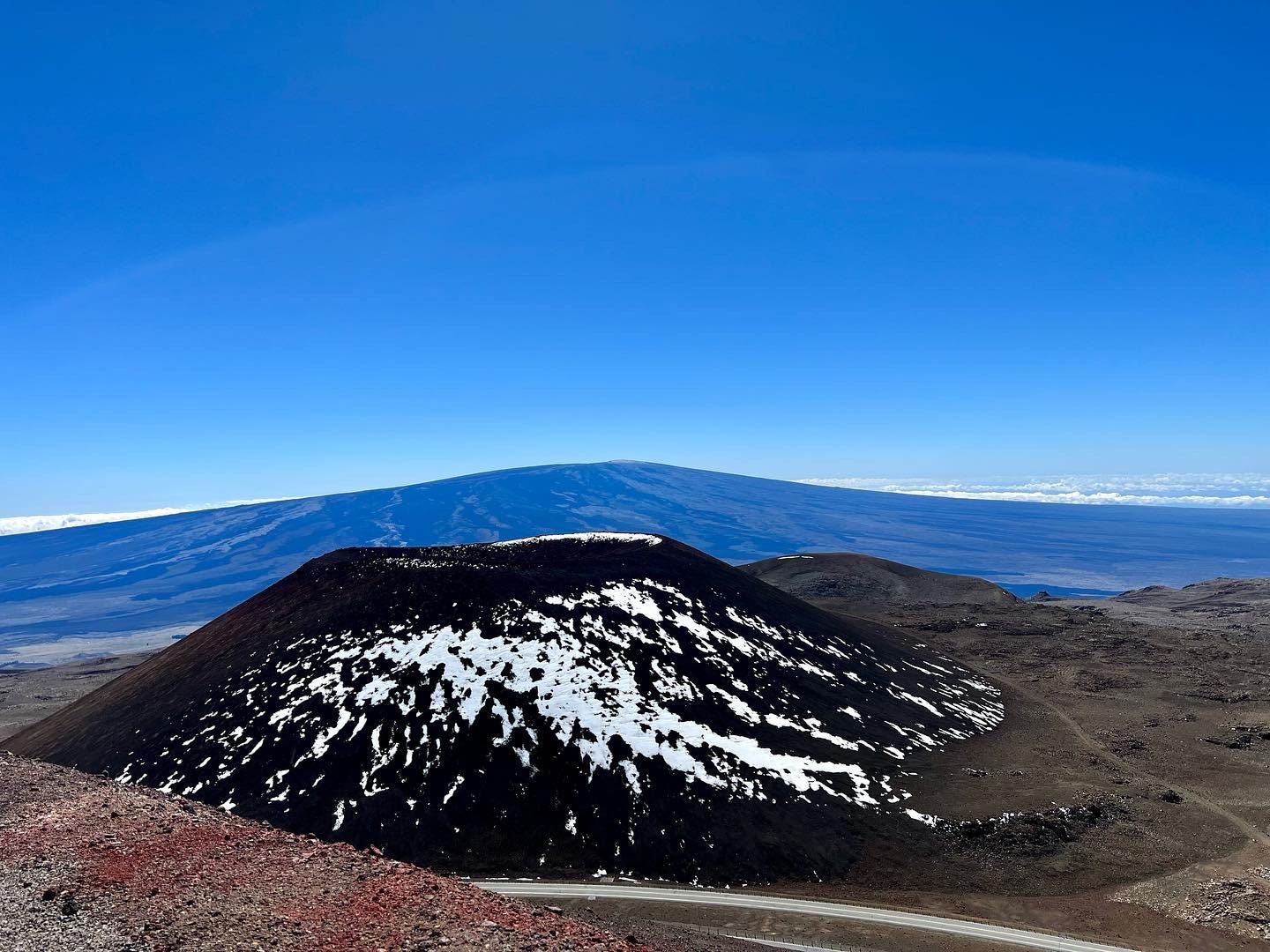

I claimed a new state highpoint in January—the Aloha State! I bet many of you didn’t realize that it snows in Hawaii, but 13,800-foot mountains tend not to play by the rules. Here’s a view from a spot near the summit of Mauna Kea, looking out over a snow-covered cinder cone. (Don’t worry, though—on this vacation I spent much more time on the beach than I did in the snow.)

FREOPP’s work is made possible by people like you, who share our belief that equal opportunity is central to the American Dream. Please join them by making a donation today.